Context Part 1

History of Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Establishment

The name "Baton Rouge" means “red stick” in French. In 1699, the Sieur d'Iberville led an exploration party of about 200 French-Canadians up the Mississippi River, and on March 17, on a bluff on the east (“left”) bank, they saw a cypress pole festooned with bloody animal and fish heads, which they learned was a boundary-marker between the hunting territories of two of the local Houma Indian groups. The bluff (by consensus among historians) is located on what is now the campus of Southern University, in the northern part of the city.

The first real settlement at the present site of Baton Rouge took place in 1718 when Bernard Diron Dartaguette received a grant from the colonial government at New Orleans. Records indicate two whites and 25 blacks (presumably slaves) resided on the concession. By 1727, however, the Dartaguette settlement had vanished; the reason for its disappearance is not known, though it probably was a combination of crop failure and the concurrent success of the settlement at Pointe Coupee, across the river and a few miles north. As the location had no particular importance to the French, they ignored it thereafter; this period of less than a decade was the sum total of Baton Rouge under French rule.

The British period

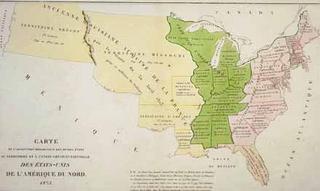

The origins of Baton Rouge as a continuously settled community date from the establishment of a British military outpost there in 1783, following the secret Treaty of Fontainbleau in the fall of 1762 that included the cession of New Orleans and western Louisiana by France to Spain and the acquisition by Great Britain of eastern Louisiana. British territory on the east was separated from Spanish lands on the west by the Mississippi from its source down to Bayou Manchac, which flows into the Amite River and then into Lake Maurepas. Baton Rouge, just north of Bayou Manchac, and now part of the colony of West Florida, suddenly had strategic significance as the southwest-most corner of British North America.

One post, named Fort Bute, was constructed on the north bank of Bayou Manchac itself, facing a comparable Spanish installation directly opposite it. A second post, Fort New Richmond, was built on the river on the present site of downtown Baton Rouge. A royal proclamation on October 7, 1763 granted the West Florida colonists “the rights and benefits of English law” and established an assembly. The colony’s first governor was Capt. George Johnstone of the Royal Navy, who was authorized to make land grants to officers and soldiers who had served in the recent war, and many of the subsequent large landholdings in the Baton Rouge area can be traced to Johnstone’s grants. (One of the earliest and wealthiest landowners, Sir William Dunbar, was granted an extensive plantation near Fort New Richmond in the early 1770s.) Planters in the Baton Rouge area were unusually prosperous, thanks both to the fertile soil and to the brisk illegal trade with neighboring Spanish Louisiana, and the fort became the center of an expanding agricultural community, though the town had not yet evolved.

The Spanish period

The Spanish periodEnglish continued to be one of the three official languages in Baton Rouge (with French and Spanish) and the Spanish administration was generally tolerant and diplomatic.

The Spanish administration ordered the building of roads, bridges, and levees, and by the late 1780s, Baton Rouge had began to transform into a flourishing town, with a population in 1788 of 682.

During the twenty years between the end of the American Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase, land-hungry American immigrants streamed into the South, including West Florida. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 did not include West Florida (or Baton Rouge), and by 1810 Spain’s position in West Florida had become completely untenable. On September 22 of that year, a rebel convention at St. Francisville deposed the Spanish governor, and ordered militia commander Philemon Thomas to seize Baton Rouge and Fort San Carlos (formerly Fort New Richmond). The following day, the fort was taken before daybreak, with two Spanish troops and no rebels killed.

On October 27, 1810, President James Madison issued a proclamation authorizing Gov. William C. C. Claiborne of Orleans Territory to take possession of West Florida, and on Decembet 10 the U.S. flag went up in Baton Rouge.

Since Louisiana statehood

On January 16, 1817, the state legislature incorporated the town of Baton Rouge and empowered it to elect a government. By 1805, two still-existing neighborhoods already had been laid out: “Spanishtown,” now in the area of Boyd Avenue near Capitol Lake, and “Beauregard Town,” bounded by North, East, and South Boulevards and the river. Spanishtown was the home of Spanish residents and those Canary Islanders who had moved into Baton Rouge from nearby Galveztown, though by 1819 many French families also had

A colony of Pennsylvania German farmers settled to the south of town, having moved north to high ground from their original settlement on Bayou Manchac after a series of floods in the 1780s. They were known locally as “Dutch Highlanders” and today’s Highland Road cuts through their original indigo and cotton plantations. The Kleinpeter and Staring families have been prominent in Baton Rouge affairs ever since.

The first steamboat, the New Orleans, landed at Baton Rouge in January 1812 and the town’s prosperous economy subsequently became highly identified with the river traffic. In 1822 alone, more than eight steamboats, 175 barges, and several hundred freight-carrying flatboats tied up at Baton Rouge’s wharves.

Baton Rouge’s location also continued to be a strategic consideration, and between 1819 and 1822 the War Department built the Pentagon Barracks near the site of old Fort San Carlos as quarters for an infantry regiment; much of the construction was supervised by Lt. Col. Zachary Taylor. In the 1830s, a federal arsenal was built near the barracks, on the grounds of the present state capitol. After the Mexican War, with the westward movement of the frontier, the military presence in Baton Rouge dwindled in importance. The Pentagon Barracks was later acquired by the state of Louisiana and has served as dormitories for LSU, as state offices, and as apartments for high-ranking state officials and employees, including (at present) the lieutenant-governor.

Baton Rouge’s location also continued to be a strategic consideration, and between 1819 and 1822 the War Department built the Pentagon Barracks near the site of old Fort San Carlos as quarters for an infantry regiment; much of the construction was supervised by Lt. Col. Zachary Taylor. In the 1830s, a federal arsenal was built near the barracks, on the grounds of the present state capitol. After the Mexican War, with the westward movement of the frontier, the military presence in Baton Rouge dwindled in importance. The Pentagon Barracks was later acquired by the state of Louisiana and has served as dormitories for LSU, as state offices, and as apartments for high-ranking state officials and employees, including (at present) the lieutenant-governor.A yellow fever epidemic decimated the Spanish-speaking community of Baton Rouge in 1828 and the death toll in a cholera epidemic in 1832 is estimated at more than fifteen percent of the town’s population.

The late 19th & early 20th centuries

The mass migration of ex-slaves into urban areas in the South also affected Baton Rouge. It has been estimated that in 1860, blacks made up just under one-third of the town’s population.

By 1880, Baton Rouge was recovering economically and psychologically, though the population that year still was only 7,197 and its boundaries had remained the same. Increased civic-mindedness led to the development of more forward-looking leadership, which included the construction of a new waterworks, widespread electrification of homes and businesses, and the passage of several large bond issues for the construction of public buildings, new schools, paving of streets, drainage and sewer improvements, and the establishment of a scientific municipal public health department. At the same time, LSU moved from New Orleans to temporary quarters at the old arsenal and barracks. Finally, legal challenges to the Standard Oil Company in Texas led its board of directors to move its refining operations in 1909 to the banks of the Mississippi just above town; Exxon is still the largest private employer in Baton Rouge.

For more information please go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baton_Rouge,_Louisiana.

Photo Thanks to: http://www.fhl.org/advocacy/lostbr/index.html.

http://www.chrisandmicah.com/albums/DowntownBatonRouge/res21789.jpg.

http://www.iadb.org/EXR/cultural/catalogues/orleans/french_period_sp.html.

http://www.cclockwood.com/stockimages/batonrouge.htm.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home